Is the Moon a Vessel?

Ethnographic impressions from Lesvos

“When I came I was full of hope. It lasted for a week, then the stress began again. The horizon of hope keeps moving”

"What could a vessel be?" asks academic writer Christina Sharpe. “Is a house a vessel? Is a nation?"(1).

Since 2015, hundreds of thousands of people have arrived by boat to the shores of Lesvos. But what do they encounter there? In September 2023, Alaa Kassab and I conducted a brief research trip to the Greek Island. Alaa is a documentary maker from Damascus, based in Copenhagen and Berlin. Inspired by Ursula Le Guin’s essay, The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction (2), we envision this page as a carrier bag. Through a collection of short texts and audio/visual fragments, we hope to convey an impression of the current reality in Lesvos among some of the people on the move.

Octopuses drying in the port of Molivos

In the Horizon

In 2015, Alaa made the journey from Turkey to Greece himself. Two years later, he returned to Lesvos to work with Doctors without Borders, assisting people arriving by boat. Back then, Molivos in the Island's north was a hotspot for new arrivals. Now, most traces have vanished. Only an olive-green rubber boat marked “Frontex” reveals that the glittering sea constitutes a border.

We drive into the stony, dry hills surrounding Molivos, searching for The Lifejacket Graveyard – a resting place for belongings that ended up in the sea or were left behind by people who reached the shore (3).

Though it must be nearby, we don’t find the Lifejacket Graveyard. Perhaps it, too, has been erased, along with other traces. It darkens. A shepherd leads his sheep to shelter as the landscape glows in the setting sun. Far away on the horizon, we can glimpse Turkey—the same horizon where Alaa once saw boats approaching.

Boats in the horizon

An Echo of Moria

"Ruins and remains of the burnt Moria Camp," the GPS announces as we approach. Moria Refugee Camp was established in 2013 to accommodate around 3,000 people. However, by 2020, during the Covid-19 pandemic, approximately 20,000 people were living here. It was the largest refugee Camp in Europe, situated in a desolate area, surrounded by olive trees.

At night, on September 8th, fires broke out, reducing the Camp to nearly ashes (4). Alaa received this video from a collaborator living in Moria in the spring of 2020, six months before the fires. It depicts the food line for the men.

Moria Camp, March 2020

Moria Camp, September 2023

What remains of Moria Camp are a few roofless white barracks, ghostly, fire-scarred trees, and scattered belongings like a couple of baby chairs. A larger area is cordoned off with barbed wire. A chapel still stands with prayer carpets and a deteriorating image of Jesus. “This place needs a worn out God”, Alaa says after looking around.

As we walk among the ruins, I think of the composer Pauline Oliveros. She created Deep Listening meditations, inviting us to connect with our sonic environment and expand the boundaries of our perception (5). Although Moria is now largely reclaimed by other species, it feels as if I can hear the echoes of the footsteps once taken here. As if all the voices, cries, and human activities still resonate.

Farden, Hamed and Jamshid

Making dreams

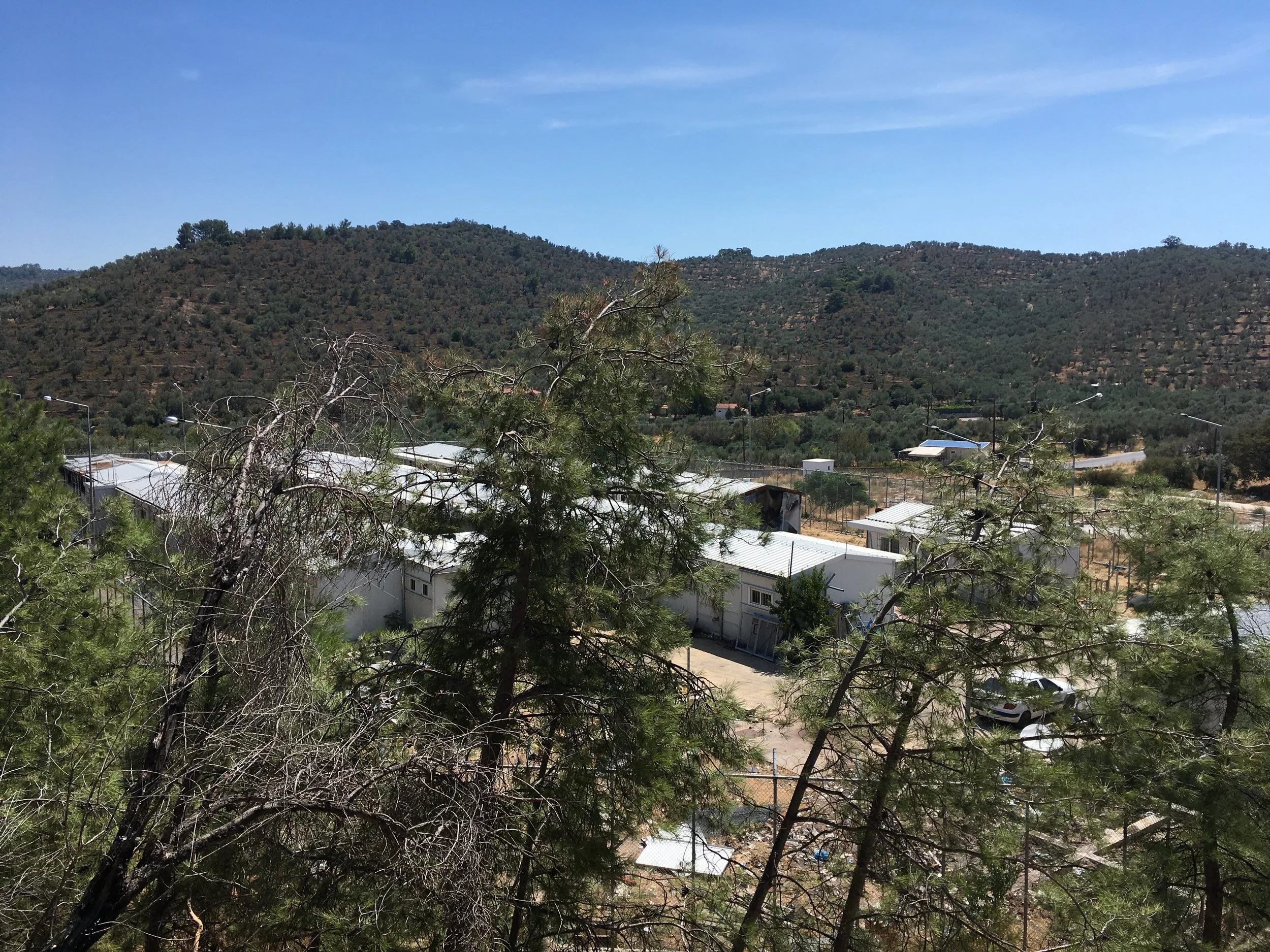

Moria Camp has been replaced by the temporary Camp, Mavrovouni. It is located by the sea, close to Mytilini, the biggest city in Lesvos. The Camp is enclosed with barbed wire, with a checkpoint at the entrance. We attempt to enter and are asked to wait in an office. From here, we observe: White tents and containers gleam in the sunlight. A large crowd of people waits outside a tent, each carrying brightly colored plastic folders with papers inside. A young girl wears a T-shirt saying “Laughing together is life”. Names are called out. A truck with armed police and security personnel is stationed a few meters away. A man tells us he has been waiting for eight hours. Suddenly, the situation becomes tense. We are told that we are not allowed to be here and are promptly escorted out by the police.

The new, temporary Camp, Mavrovouni

Outside the Camp, three young men sit in the shade with their bicycles, preparing to head to Mytilini. They are from Afghanistan, and one of them, Farden, speaks English. Later, we meet them for pizza and sodas in a Parque buzzing with cicadas.

Farden, who is 19, arrived in Lesvos three months ago. He lives in an ISObox (a container) with his parents, sister and younger brother. His older brother left for Europe alone at the age of 13. The brother passed some time in Moria, and now lives in a shelter in Germany. Farden wears a bracelet with his name on it; it's all he has left after losing his belongings during the boat trip. The family hopes to reunite with his brother in Germany.

Jamshid, who is 17, lives with his sister in the camp. His father passed away and his mother and brother are in Iran. His dream is that they can all go to Germany and be together there.

Hamed,18, made multiple attempts to cross the sea between Turkey and Greece. He has been living with his parents in the camp for more than a year. They also hope to continue to Germany, where they have relatives.

All three are passionate about sports. Jamshid and Hamed are into boxing, while Farden plays football. They dream of becoming professionals.

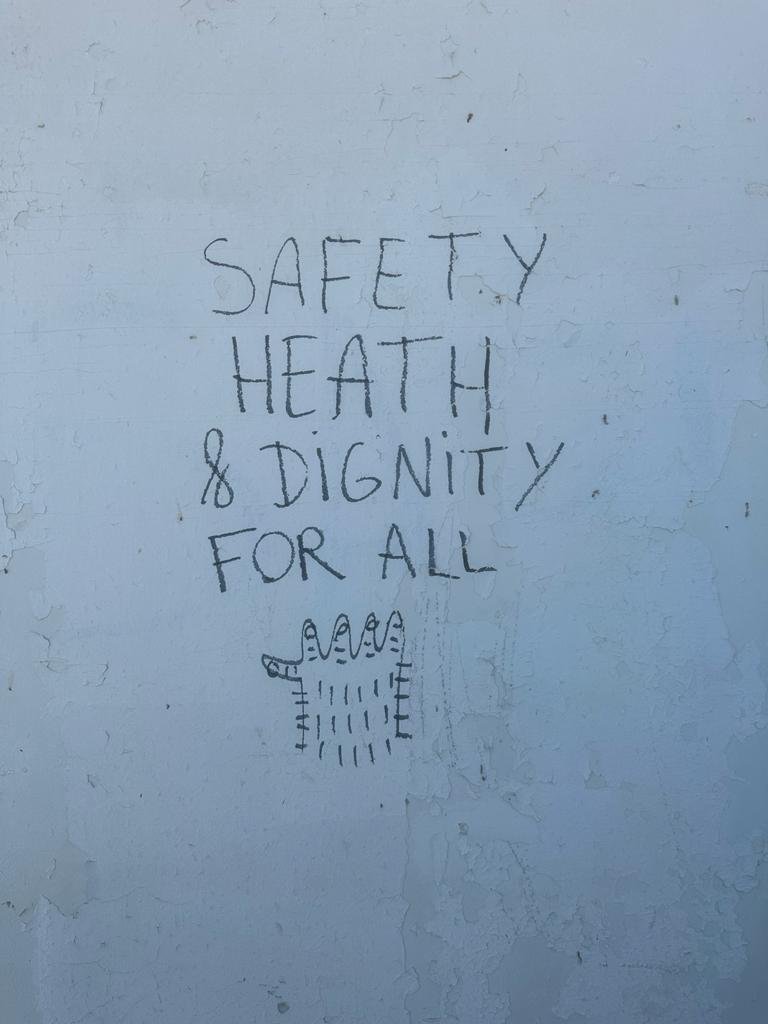

“The camp is closed, but we have very open dreams. Every day, we make our dreams inside our minds.”

At the barber. Photo: Farden

In the audio files, Farden tells about their life inside the Camp.

He describes the daily routine of waiting for hours in the food line and talks about friendship. They used to be four friends. Now, one has left, and Hamed has been informed that he and his family will soon be transferred to another Camp.

Mavrovouni Camp is noisy, and the longing for peace and silence is immense. The mosque within the camp provides such a space. Sometimes, Farden, Jamshid, and Hamed visit to pray or rest. They also treasure a special spot by the sea. After the camp quiets down around midnight, they gather here with friends, play soft music, and share their dreams. In this way, they create their own sensory environment, whose soothing atmosphere contrasts sharply with the bustling camp. It is a space where they can actively "make dreams," as Farden expresses it—a shared envisioning of their desired futures.

From this special spot by the sea, they can hear the sound of the waves. Occasionally, when the moonlight glimmers upon the sea, it evokes memories of their journey from Izmir to Lesvos.

This evening, as we drive from Mytilini, the moon rises, full and glowing orange above the sea. Listening to Farden, made Alaa, recall his own trip: "He went the same route, from the same point in Izmir in Turkey. When he mentioned the moon I was inside smiling. The moon has been helpful to many vulnerable souls.”

What is a Vessel for holding this?

We now return to the question posed in the beginning by academic writer Christina Sharpe: “What could a vessel be?” This inquiry serves as the title of Sharpe’s keynote speech at the Venice Biennale in 2022. Alongside one section within the Biennale, her speech draws inspiration from Le Guin's The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. Sharpe delves into the concept of the vessel, both as an abstract idea and a tangible object, aiming to grapple with the multiple crises of our time and directly confronts the refugee catastrophe with a series of questions.

We have taken the liberty of quoting fragments of Sharpe’s speech in this video (6).

What could a Vessel be?

“It will be difficult for people who come tonight. When the sea is turbulent, they send people, because there is less vigilance.”

Different Cartographies

The arrival spots have shifted in Lesvos since Alaa worked on the Island. Now, the boats primarily reach the coast near Mytilini. The beach here is narrow and stony, positioned by the road leading to the airport. From this vantage point, we can see Turkey.

We go swimming with Farden, Hamed, and Jamshid. It’s a windy day. A ladder leads down to the sea. The waves are big, leaving a salty taste in our mouths. Hamed is a good swimmer, while Farden and Jamshid are still learning. “It will be difficult for people who come tonight,” Farden says as we sit in the sun to dry off. “When the sea is turbulent, they send people, because there is less vigilance.”

In the evening, back at our guest house, Alaa and I go for a second swim with the other tourists. “We all swim in the same sea,” Alaa says as we walk out into the water.

At night, I lie awake listening to the waves crashing against the shore. The rhythm is strong, almost like a pulse. I think about the people out there, the ones at sea. About Farden and his friends. And I think about how, when it comes to receiving peoples stories, Alaa and I carry different cartographies of knowledge.

My map is sparse. I carve out small lakes of insight, tiny hills of understanding – but a vast terrain is filled out largely by my imagination. In contrast, Alaa’s map is densely packed with lived experiences, a complex topography with layers of depth. Perhaps even subterranean caverns.

At day, I propose this idea to Alaa. He replies: “Sometimes I wish my map was more empty.”

A Border in Motion

September marks the end of the journeying season. With the approach of Autumn, numerous people, primarily from Afghanistan, arrive to Lesvos. The sea literally embodies a border in motion. The Greek authorities have started to push back boats, even after people have reached the shore. These illegal actions increase the peril and uncertainty of the journeys.

As Europe’s gateway, Greece finds itself in a vulnerable position. The huge arrival of people to Lesvos has significantly impacted the Island's local population. With the decline in tourist numbers, many have witnessed their primary sources of income vanish. This economic strain may partly explain the Greek authorities' efforts to block and obscure the presence of people on the move. Right now, plans for a new permanent Camp, a “Closed and Controlled Center”, are underway. It will be situated in Vastria, a remote, uninhabited area at the heart of the Island.

Farden, Jamshid and Hamed introduce us to Parea, a Cultural Center near the Camp. The Center offers a garden with shaded spots, a workshop for bike repairs, and a space exclusively for women. Volunteers engage in various activities, play board games, and prepare food. “We aim to create a haven where people can feel at home, contrasting with the camp's harsh environment,” says Silva Lucibello, the Center's coordinator. In the audio file Silvia tells about the conditions inside the Camp.

The body is a Vessel

Here is another fragment of Christina Sharpe’s speech “What could a Vessel be”?

The body is a vessel

A silent encounter

In Parea, I meet Hadisha. She is sitting on a shady bench, wearing a red flowered dress, sunglasses, a scarf, and a wide-brimmed sun hat. “I take care of my skin,” she says. Together, we go to the women's space where beauty products are placed on a table. Hadisha paints my fingernails and draws a red flower with henna on my forearm. When she applies the nail polish, she tells me she can forget her worries. Her thoughts disappear, and she can relax.

I relax too. In Lesvos, I struggle to sleep at night. During the day, exhaustion clouds my thoughts. All the questions I had, or thought I should have, dissolve. But it feels okay to be quiet with Hadisha – as if a silent confidentiality rises between us.

We leave the women's space. Hadisha picks up food and we return to the shaded bench. Here, she shares her meal with me, and after a while, she starts to talk. She tells me she is stressed and suffers from migraines. She can't sleep at night. They are six women in a tent meant for four people. Not all of them have a bed. And the heat! It is so warm. There is no air conditioning. In the mornings, she prays and drinks a cup of coffee outside the tent. Then, she seeks shade and silence. As a single woman, she doesn’t feel safe in the Camp. She hates the noise and the food line. She does not know what to do with herself.

She pauses, and we sit together quietly for a while. Then she speaks again, about the events that happened before she arrived in Lesvos, about the people she lost. After each pause she dives deeper into details. No questions are needed. The silence between us is a vessel.

Photos by Hadisha

The Moon is a Vessel

Inspired by Christina Sharpe’s speech, and drawing from our experiences in Lesvos we ask:

“What could a vessel be?”

What is a vessel when people set out at night to cross a turbulent sea?

Is a vessel an inflatable piece of rubber?

Is a vessel a destination?

Are leaving and longing the same?

What is or should or could a vessel be, when boats are pushed back into the sea after they've reached the shore?

Is prayer a vessel?

Is knowing how to swim a vessel?

Is a vessel a declaration of Human Rights?

What is a vessel when 3,000 people stand in line for hours daily, in a camp devoid of shade and safety?

Are documents a vessel?

Is making dreams a vessel?

Are waiting and withering the same?

Friendship is a vessel.

The moon is a vessel.

What else could a vessel be,

at the end of this world?

Thank you

Ten months have passed since our trip to Lesbos until the release of this page. Jamshid and Hamed are now in Germany. Farden and his family are still in Greece, where Farden studies and works as an interpreter with the organization IHA (InterEuropean Human Aid Association). It has not been possible to stay in touch with Hadisha.

A huge thank you to Farden, Jamshid, Hamed and Hadisha. Also thank you to Silvia Lucibello, and to Christina Sharpe.

A special thank you to Alaa Kassab for the collaboration

The project is funded by:

The Sensory Media Anthropology Network (NOS-HS)

Notes and bibliography

1 Sharpe, Christina (2022) What could a vessel be?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4BYPvgRJGQg

2 Le Guin, U. K. (1988) The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. Dancing at the Edge of the World: Thoughts on Words, Women, Places. New York: Grove Press.

3 https://crisisandenvironment.com/lifejacket-graveyard/

4 https://forensic-architecture.org/investigation/fire-in-moria-refugee-camp

5 Oliveros, Pauline (2005) Deep Listening. A Composer’s Sound Practice. New York: Deep Listening Publications

Oliveros, Pauline (2011) Auralizing in the Sonosphere: A Vocabulary for Inner Sound and Sounding In: Journal of Visual Culture. Vol. 11 (2)

6 The idea for the call and response and fragmented reading is borrowed from this podcast:https://tinhouse.com/podcast/crafting-with-ursula-lidia-yuknavitch-on-the-carrier-bag-theory-of-fiction/